Laggard to Leader: a Review

MCJ Posted on

MCJ Posted on  Tuesday, July 24, 2012 at 11:37

Tuesday, July 24, 2012 at 11:37 Beyond Zero Emissions, the non-for-profit climate change group, yesterday released the latest in their series of plans to get Australia to a state of zero emissions (or below): Laggard to Leader; How Australia can lead the world to zero carbon prosperity.

The report springs from the observation, also reported by e.g. Crikey on Friday, that the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change is failing to achieve the actions required to prevent dangerous anthropogenic climate change. It then goes beyond this to suggest new means of addressing the problem, in which Australia leads the world to a zero carbon future.

Sound utopian? It’s actually reasonably well argued, by and large, even if it’s difficult to see our current crop of politicians implementing many of the report’s suggestions.

Laggard to Leader begins with a summary of the scientific need for action: if we want to constrain the rise in global temperatures to 2°C, then the world shouldn’t emit more than 550 gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon-dioxide-equivalent (CO2-e) greenhouse gases by 2050. Why 2°C? Because the really worrying thing about climate change is that the relationship between greenhouse gases and temperature could become non-linear, i.e. small emissions = big temperature rise; this is estimated to occur somewhere between 2°C and 5°C.

On current projections, Laggard to Leader estimates the world will emit those 550 GtCO2-e by 2025 and warm by 6°C by the end of the century. With this metaphorical fire under our backsides, what is the world doing about it? Not nearly enough, writes the report, providing a very useful potted history – for those who don’t subscribe to international policy journals – of UN climate negotiations, the tactics involved, and the flaws in their outcomes; Australia in the 1990s, for example, made sure to maximise the scope of land-based emissions removals it could count as credits, while minimising those sources counted as debits; Russia and other ex-soviet states received billions of emissions credits made unnecessary by their unexpected deindustrialisation; and the USA and China seem to be engaged in a game of ‘abatement chicken’.

Having argued fairly convincing that the current top-down “treating, targets, and trading” paradigm is failing, Laggard to Leader suggests an alternative approach: countries engage in “Cooperative Decarbonisation”, in which “each country [phases] down to zero or very near zero the greenhouse gas emissions associated with every economic and social process over which it has control or influence.”

This “control or influence” argument – described as the “’sphere of influence’ approach” – is crucial for the rest of the report, as it establishes the rationale for claiming that Australia’s (and other countries’) responsibilities aren’t confined simply to the emissions produced domestically. The chapter worth reading in full, but a central point is that a focus on domestic emissions only makes sense in the context of a comprehensive, legally binding, and effectively enforced global regime of emissions reduction targets – which clearly isn’t the current situation.

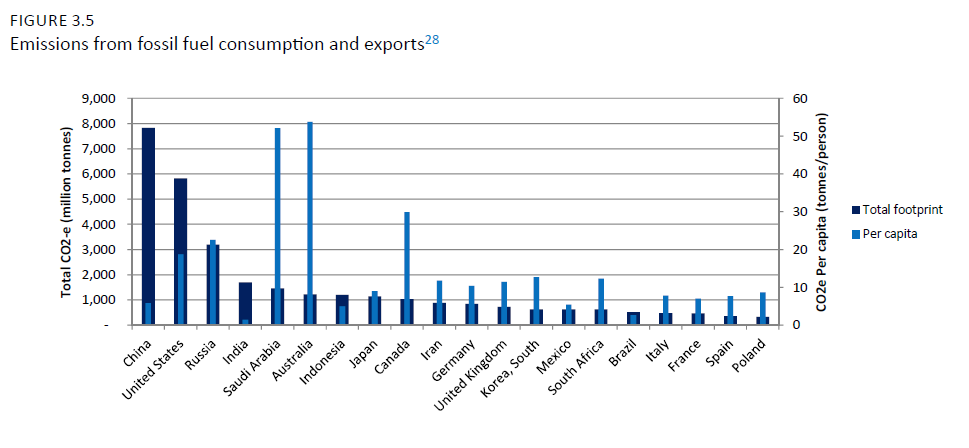

Under the perhaps second-best but more realistic scenario of distributed or bottom-up action, the scope of emissions under Australia’s “control or influence” (and therefore those for which we bear at least partial responsibility) is staggering: 4% of the world’s emissions, primarily due to our fossil fuel exports.

Laggard to Leader, p. 20

Having established the scope for action – from a scientific and moral standpoint – the rest of Laggard to Leader describes in more detail the “Cooperative Decarbonisation” approach, exploring both domestic and international policy options.

It’s ambitious stuff: countries should form cooperative groups based on the goal of tackling particular causes of climate or the developing and deploying zero-carbon technology, with each group containing those countries with the greatest needs and capacities for help (and interest in participating). Where cooperation fails, countries should go it alone.

Countries should build a “race-to-the-top” culture, establishing norms and standards of conduct for the non-use of fossil fuels, as exist for e.g. nuclear testing and anti-personnel landmines, or, more formally, moratoria on mining in Antarctica and the use of nuclear weapons. Here Laggard to Leader provides past examples of Australian international leadership, arguing that we have an historical identify as a leader and are socially recognised as such by other states.

Between this ‘social’ position, our market-leading position in the fossil fuel trade – Australia is the world’s top coal exporter, and expected to be the top LNG exporter by the end of the decade –, and our high wealth, Laggard to Leader argues that we are in an almost unique position to decarbonise quickly, help developing countries do the same, and play a leadership role in facilitating international cooperation.

Under this plan, Australian fossil fuel exports (and domestic usage) should be phased out entirely, while providing assistance to developing countries to help them replace the fossil fuels with zero-carbon technology. Australia should price international flight and shipping emissions on transport to our shores, as well as implement border tax adjustments for goods whose greenhouse gas content is not adequately priced in source countries. And we should significantly ramp up investment in zero-carbon research, development, and deployment.

Much of Laggard to Leader is, if taken in isolation, not that controversial. If you accept the science, then the need for action is fairly self-evident, and the technology and policies described in the latter part of the report have been an on-going area of discussion between and within academia, industry, and government for a while. What sets Laggard to Leader apart and moves it into uncomfortable territory is – as with many of BZE’s publications – the marriage of technical possibility with ambition at a grand scale. Many won’t like the conclusions, and thus dismiss the whole report, but the argumentation is strong enough that Laggard to Leader’s conclusions bear consideration. Grand ambition may be our best hope.

I was not involved in writing Laggard to Leader, but provided feedback on an early draft.

Laggard to Leader is being launched tonight (24/07) in Sydney, and on Thursday (26/07) in Brisbane.

MCJ

MCJ

The lead authors of Laggard to Leader, Fergus Green and Reuben Finighan, have related media pieces in RenewEconomy and the Lowy Interpreter.

Australia,

Australia,  BZE,

BZE,  climate change,

climate change,  policy

policy

Reader Comments (2)

Yes, the report bravely puts a peg in the ground waaay over there. By doing this, it may change the map and make some other positions look less extreme!

The report draws a parallel with Australian leadership wrt nuclear proliferation, but this is a very imperfect comparison. Australia wasn't a player in the nuclear race, whereas it is a very big player in the coal and gas export business.

I suspect that if Australia put a moratorium on new coal/gas exports, the closer parallel would be OPEC actions in the 1970s. And the results may well be similar - a shock would reverberate around the world. Not just a media shock, but an economic shock too.

How do you see this?

Gillian,

Laggard to Leader draws many parallels with past examples of Australian international leadership, of which the nuclear proliferation example is only one. I think the example is better than you give it credit for: you say Australia wasn't a player in the nuclear race, but is a big player in coal/gas exports – that's comparing two different things. Australia may not have been a player in the "nuclear race", but that race was about the construction and use of nuclear technology, not the export of fuel for that technology. A more apt comparison would be Australia's export of uranium at the time of its actions.

While I don't have the historical records of Australia's uranium exports to hand, Wikipedia tells us that Australia has (by far) the world's greatest reserves of uranium as well as the highest historical production.

I do agree that moratoria on fossil fuel exports would create economic shocks, but the difference to OPEC in the 1970s would be (presumably) the time-scale over which such a decrease in volume occurred and the ability to replace coal and gas with alternative fuels. Both these factors would, I hope, mitigate any economic shocks, particularly the second factor.

What I didn't see in Laggard to Leader was much discussion of the possibility that we – Australia and our customers – would not be able to sufficiently replace fossil fuels with renewable technologies to maintain our current(ly desired) patterns of consumption, and may be forced into lifestyle change as a result of said moratoria. Perhaps this was a step too far in terms of uncomfortable topics. (Equally as likely, the authors simply didn't have the time to address it, as they didn't address emissions from imports.)

N.B. 'Patterns of consumption' and 'lifestyle' are not the same as 'standard of living'; nor is there necessarily an imperative to maintain any current standard of living if the future costs are too high.